Beijing’s Naval Posture in the South China Sea: A Post-Pandemic Update

This short paper seeks to highlight key updates on naval developments in the SCS since the start of COVID-19. But why specifically “naval” when coastguards appear to be on the front page of recent incidents in the disputed waters? The key development of concern here is how the PLA Navy has become a more assertive actor in Beijing’s quest to push its maritime sovereignty and rights in the SCS. The Southern Theater Command Navy is tasked with both SCS sovereignty and rights protection, and covering Taiwan in times of war. In recent times, this fleet has become a focus of attention for an intensified spate of military exercises, often with sister PLA service as part of the tit-for-tat posturing and counter-posturing against American military activities in the SCS. But while this fleet is generally restrained where it comes to ‘counter-presence’ operations directed at regular foreign military presence in the SCS, the same cannot be said of its apparent growing prominence in asserting China’s maritime sovereignty and rights.

By Collin Koh

September 12, 2022

This short paper seeks to highlight key updates on naval developments in the SCS since the start of COVID-19. But why specifically “naval” when coastguards appear to be on the front page of recent incidents in the disputed waters? To be sure, coastguards remain key actors in the SCS disputes, as witnessed in the events since the late 2019 before the pandemic outbreak – notably, the incident involving Chinese seismic survey vessel Haiyang Dizhi No. 8 in Vietnam’s exclusive economic zone – and a string of Chinese maritime coercion instances from 2020 onwards. And not forgetting, of course, Beijing’s promulgation of a coastguard law in February 2021 which would allow its maritime forces to respond with force where applicable to foreign transgressions.

It is a foregone conclusion that Beijing has a huge lead in coastguard capacity vis-à-vis its Southeast Asian SCS rivals and looks set to keep widening this power asymmetry. But it is in the naval realm where some seismic shifts are taking place with regard the SCS dynamics taking place lately. And these are not necessarily high-profile PLA Navy induction of new assets in the SCS, for example, the late 2019 basing of China’s second aircraft carrier Shandong,[i] or the unprecedented simultaneous commissioning of the PLA Navy’s first Type-075 landing helicopter, dock Hainan, as well as the Type-055 guided missile destroyer (classified by some as cruiser) Dalian in April 2021.[ii]

Rather, the key development of concern here is how the PLA Navy has become a more assertive actor in Beijing’s quest to push its maritime sovereignty and rights in the SCS. The Southern Theater Command Navy is tasked with both SCS sovereignty and rights protection, and covering Taiwan in times of war. In recent times, this fleet has become a focus of attention for an intensified spate of military exercises, often with sister PLA service as part of the tit-for-tat posturing and counter-posturing against American military activities in the SCS. But while this fleet is generally restrained where it comes to ‘counter-presence’ operations directed at regular foreign military presence in the SCS, the same cannot be said of its apparent growing prominence in asserting China’s maritime sovereignty and rights.

Stepping Up Sovereignty and Rights Assertion Posture

The PLA Navy’s SCS forces used to perform the role of maritime sovereignty and assertion in the disputed waters until Chinese maritime law enforcement agencies, such as the China Coast Guard, expanded their capacities to undertake this function. A fully equipped warship bristling with heavy, offensive armaments would not have been the preferred choice in the first place since Beijing would be keen to be perceived as avoiding destabilizing peace and stability in the SCS. Moreover, it would make better sense for the navy to devote its assets and manpower to tasks such as peacetime training and defense diplomacy instead. The CCG and its predecessors would therefore front for Beijing in the SCS while the navy recedes to the background, providing what one may call “recessed deterrence” as a backup. In recent years, however, this seems to have changed.

Within the CCG community there appears to have been growing concerns about the efficacy of China’s approach to maritime sovereignty and rights protection in the SCS. The first issue pertains to the lack of a comprehensive, unified maritime legislation that would pull together the disparate laws for specific maritime functions (e.g. marine environmental protection and fisheries management), with the other being the use of naval forces by Southeast Asian rivals in the SCS.[iii] That Southeast Asian SCS parties deploy navies for constabulary missions is nothing new – with many continuing to do so despite the existence of their coastguards, such as for example Indonesia and Malaysia.[iv] This mainly stems from the fact that only the navies possess appropriate assets and available capacity for such taskings.

But this situation appears to have posed a challenge for the CCG given how the Southeast Asian naval vessels are generally on par in terms of physical size, which allow them to maintain station for sustained periods out at sea. Even if some of these warships are physically smaller than the ships fielded by the CCG, they are comparatively more heavily armed.[v] The CCG therefore sought to rectify the situation, with the most straightforward route being to build better-armed patrol vessels. In addition, the CCG also embarked on the more expeditious route of acquiring more warships from the PLA Navy for conversion into patrol vessels.[vi]

The other approach undertaken by China in recent times is a more robust naval posture to assert its SCS sovereignty and rights.[vii] This has been in the works for some years, with initial experiments carried out to this effect. Notably in May 2018, the PLA Navy, CCG and local maritime law enforcement authorities constituted a joint flotilla to conduct patrols in the Chinese-occupied Paracel Islands for the first time. This arrangement provided for a graduated response to contingencies at sea: if the flotilla were to encounter a foreign naval vessel, the PLAN ship would respond; the CCG ship would deal with foreign fishing vessels; whereas the local authorities focus on Chinese nationals (such as fishermen, smugglers) who violate domestic maritime laws.[viii]

It is plausible to believe that this new arrangement is no longer just confined to the Paracel Islands; instead, it may have already been extended to the Spratly Islands group and other contested features nearby. And incidents since the COVID-19 outbreak appear to have validated this step-up in China’s SCS naval posture. Notably in April 2020 for instance, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) revealed that in February that year, a PLA Navy ship (identified by its hull number 514, which is the Type-056 missile corvette Liupanshui based in Sanya) exhibited “hostile intent” when it pointed a “radar gun” at a Philippine Navy corvette BRP Conrado Yap close to Commodore Reef within the Philippine-claimed EEZ.[ix]

Though there was no untoward eventuality from the incident, it had become apparent that more than just providing backup for the CCG, the PLA Navy has adopted a more assertive posture in its SCS sovereignty and rights protection missions, and begun to actively challenge rival naval forces in the disputed waters. The Chinese ‘joint flotilla’ patrol arrangement was replicated during the maritime standoff with the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea following the flareup at Whitsun Reef in March 2021. From early March to April 2021, Philippine maritime patrols monitoring the swarm of Chinese vessels in the West Philippine Sea caught sight of PLA Navy vessels around various features that are part of the disputed Spratly Islands group.[x]

That same period, a pair of PLA Navy Type-022 Houbei-class catamaran-hulled missile fast attack craft worked with the CCG to pursue a Filipino television crew conducting investigative journalism in the West Philippine Sea, close to the Second Thomas Shoal where a Filipino military garrison is stationed.[xi] This incident came not long after revelations that a Philippine maritime patrol observed some Houbei craft along with a Type-904 Dayun-class supply tender were spotted at the Chinese-occupied Mischief Reef outpost within what Manila refers to as the West Philippine Sea.[xii] This was another clear sign of the PLA Navy stepping up China’s SCS sovereignty and rights protection posture.

Southeast Asian Pushback: Noteworthy But Hamstrung

Save for Brunei, which has by far yet to be embroiled in any significant SCS standoff with China, the other Southeast Asian parties have had their fair share of resistance, in some form or another, against Beijing’s maritime coercion. For instance, during the February 2020 standoff over the drillship West Capella within the Malaysian exclusive economic zone off Sarawak, the Malaysians deployed at least one ship – usually a naval vessel – as a counter against the more numerous Chinese coastguard presence.[xiii] In June 2021, after a CCG vessel appeared in the Indonesian EEZ to monitor the semi-submersible energy rig Noble Clyde Boudreaux, Jakarta immediately dispatched both naval and coastguard assets to the area in response.[xiv]

Even though China clearly possesses the advantage in terms of its physical force projection in the SCS, given its significant military and coastguard buildup in the area over the years, by no means this asymmetry of maritime forces capabilities and capacities implies its Southeast Asian rivals conceding ground. A noteworthy instance is the Philippines. Following revelations of the Whitsun Reef problem and emergence of numerous Chinese vessels, including naval and coastguard, in the Philippine EEZ in early 2021 Manila responded with vigour which marked a departure from a more passive stance taken during the early days of the then Duterte Administration. Notwithstanding capacity limitations, the Philippine Navy, Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources mobilized assets and manpower to monitor the situation.[xv]

There were also recorded instances where Philippine maritime forces boldly challenged their Chinese counterparts, despite concerns that the latter could leverage the new Coast Guard Law for retaliation. For instance, in April 2021 the Philippine Coast Guard challenged a group of Chinese fishing vessels, some of which believed to be maritime militia, off Sabina Shoal and expelled them without further incident.[xvi] In July the same year when confronted by a Philippine Coast Guard vessel BRP Cabra and issued a verbal challenge via a long-range acoustic device in waters near Marie Louise Bank (well within the Philippine EEZ), the PLA Navy fleet tug Nantuo 189 departed the area without further incident.[xvii]

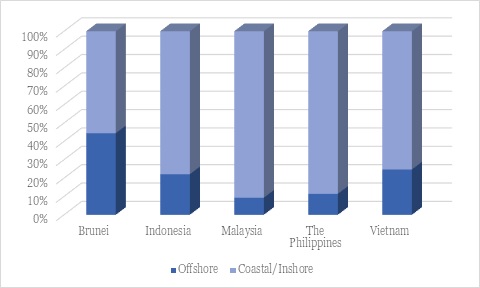

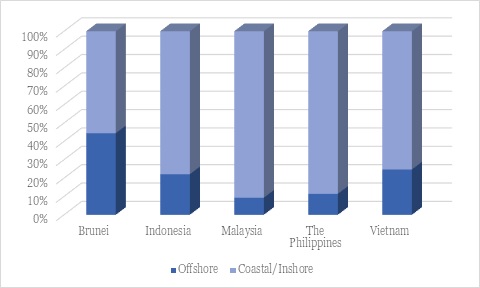

The combined quantitative might of the PLA Navy and CCG would put their Southeast Asian rivals at a distinct disadvantage. Southeast Asian military authorities have complained that not only their fleets lack capacity, but those assets in service were already ageing.[xviii] In terms of physical maritime assets, offshore-capable vessels hold the key to persistent presence in the open EEZ waters, not coastal or inshore assets.

As Figure 1 below shows, offshore-capable surface patrol and combat assets that serve navies and coastguards of Southeast Asian SCS parties have largely hovered below 30 percent of the force totals, with Brunei being an exception given its tiny fleet of nine operational vessels. The figure of course does not indicate the exact state of operability and readiness of these assets, and it does not also consider their geographical distribution. Given the long coastlines and vast maritime zones of these Southeast Asian countries (except Brunei), it is only to be expected that the available assets will have to be deployed to other areas besides the SCS.

Figure 1: Surface Patrol and Combat Vessels of Southeast Asian SCS Parties

Source: By author using data compiled from the Military Balance 2022, International Institute of Strategic Studies.

Yet the attempt to address capacity shortfalls in offshore-capable assets has been a chequered and uneven one in Southeast Asia, often determined by funding availability and the tussle between navies and coastguards for finite resources. Vietnam is perhaps one of the most prolific where it comes to maritime forces buildup, having distributed its limited funds to modernize both the navy and its maritime law enforcement agencies – the Coast Guard, and the Fisheries Resources Surveillance Force. The political will, however, is not always matched by the availability of resources and funding. For the other Southeast Asian SCS parties, maritime forces capacity-building has become a less certain prospect given prevailing post-pandemic climate.

Malaysia’s maritime forces development has been hamstrung by economic difficulties, not least the COVID-19 impact as well as procurement governance woes, which placed several key programmes on backburner – not least the Littoral Combat Ship program, which has overrun its envisaged schedule. The first of three Tun Fatimah-class offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) was supposed to have been handed over to the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency in 2019, but would only be delivered earliest in 2022.[xix] The Philippine Navy and Coast Guard have inducted more offshore-capable assets in the form of new frigates and OPVs acquired from France, Japan and South Korea. Funding constraints would prolong the process.

The Way Forward for Southeast Asian Parties

Responding to China’s maritime coercion should not be down to mere vigour while being hamstrung by capacity shortfalls. Oft-cited ways to improve Southeast Asian SCS parties’ ability to push back against China’s maritime coercion include enhancement of maritime domain awareness (MDA). For many of these Southeast Asian countries, real resource limitations in assets and manpower would mean better MDA promises more effective ways of deploying sufficient forces to where it matters most. Over the recent decade, Southeast Asian SCS parties has been a primary beneficiary to U.S.-sponsored maritime security capacity-building assistance, which in large part focuses on plugging MDA gaps, and facilitate to an extent their optimal deployment of limited maritime capacities for sovereignty assertion in the vast SCS.

Given that China has committed its coastguard forces as spearheads on the SCS frontline, there has been a longstanding push for Southeast Asian countries to expand their coastguards instead of devoting too much attention to navies. Such concerns were grounded on the assumptions that Beijing would only commit the CCG (and for that matter, its maritime militia) to the SCS operations. As highlighted earlier, given China’s more assertive use of its navy in pushing SCS maritime sovereignty and rights, Southeast Asian maritime forces capacity-building should focus on not only MDA, but beefing up physical assets of both navies and coastguards that allow for action against transgressors at sea – not least of course, putting up a viable counter-presence against China’s in the disputed waters.

At present, extra-regional powers are gradually scaling up the game where it comes to supply of physical assets besides MDA, such as the case of the transfers of former U.S. Coast Guard cutters to Vietnam, Japan’s provision of used and newbuild OPVs to Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. Yet there remains outstanding needs for Southeast Asian SCS parties to fill this capacity gap. The asymmetry in maritime force levels between these countries and China looks set to persist. Transfers and newbuild constructions aside, measures to help these Southeast Asian countries spruce up their local shipbuilding capacities, such as through funding, technology transfers and other technical assistance will be helpful in allowing them to become more self-sufficient in building their own OPVs.

Physical capabilities to push back against China’s maritime coercion is one thing though, other pressing aspects quite another. Given the blurring nexus between China’s naval and coastguard forces in the SCS, it becomes all the more imperative upon Southeast Asian countries to relook into and enhance their inter-agency maritime efforts. One may take comfort in the fact that some of the Southeast Asian SCS parties have recognized and getting started in improving on this aspect.[xx] Still, it remains a long, uneven road of work in progress across these Southeast Asian players. It is therefore important to give a renewed emphasis on this dimension.

Collin Koh Swee Lean is research fellow at the Maritime Security Programme, at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, based in Singapore. He primarily researches on Indo-Pacific maritime security and naval affairs, focusing especially on Southeast Asia.

Notes

It is a foregone conclusion that Beijing has a huge lead in coastguard capacity vis-à-vis its Southeast Asian SCS rivals and looks set to keep widening this power asymmetry. But it is in the naval realm where some seismic shifts are taking place with regard the SCS dynamics taking place lately. And these are not necessarily high-profile PLA Navy induction of new assets in the SCS, for example, the late 2019 basing of China’s second aircraft carrier Shandong,[i] or the unprecedented simultaneous commissioning of the PLA Navy’s first Type-075 landing helicopter, dock Hainan, as well as the Type-055 guided missile destroyer (classified by some as cruiser) Dalian in April 2021.[ii]

Rather, the key development of concern here is how the PLA Navy has become a more assertive actor in Beijing’s quest to push its maritime sovereignty and rights in the SCS. The Southern Theater Command Navy is tasked with both SCS sovereignty and rights protection, and covering Taiwan in times of war. In recent times, this fleet has become a focus of attention for an intensified spate of military exercises, often with sister PLA service as part of the tit-for-tat posturing and counter-posturing against American military activities in the SCS. But while this fleet is generally restrained where it comes to ‘counter-presence’ operations directed at regular foreign military presence in the SCS, the same cannot be said of its apparent growing prominence in asserting China’s maritime sovereignty and rights.

Stepping Up Sovereignty and Rights Assertion Posture

The PLA Navy’s SCS forces used to perform the role of maritime sovereignty and assertion in the disputed waters until Chinese maritime law enforcement agencies, such as the China Coast Guard, expanded their capacities to undertake this function. A fully equipped warship bristling with heavy, offensive armaments would not have been the preferred choice in the first place since Beijing would be keen to be perceived as avoiding destabilizing peace and stability in the SCS. Moreover, it would make better sense for the navy to devote its assets and manpower to tasks such as peacetime training and defense diplomacy instead. The CCG and its predecessors would therefore front for Beijing in the SCS while the navy recedes to the background, providing what one may call “recessed deterrence” as a backup. In recent years, however, this seems to have changed.

Within the CCG community there appears to have been growing concerns about the efficacy of China’s approach to maritime sovereignty and rights protection in the SCS. The first issue pertains to the lack of a comprehensive, unified maritime legislation that would pull together the disparate laws for specific maritime functions (e.g. marine environmental protection and fisheries management), with the other being the use of naval forces by Southeast Asian rivals in the SCS.[iii] That Southeast Asian SCS parties deploy navies for constabulary missions is nothing new – with many continuing to do so despite the existence of their coastguards, such as for example Indonesia and Malaysia.[iv] This mainly stems from the fact that only the navies possess appropriate assets and available capacity for such taskings.

But this situation appears to have posed a challenge for the CCG given how the Southeast Asian naval vessels are generally on par in terms of physical size, which allow them to maintain station for sustained periods out at sea. Even if some of these warships are physically smaller than the ships fielded by the CCG, they are comparatively more heavily armed.[v] The CCG therefore sought to rectify the situation, with the most straightforward route being to build better-armed patrol vessels. In addition, the CCG also embarked on the more expeditious route of acquiring more warships from the PLA Navy for conversion into patrol vessels.[vi]

The other approach undertaken by China in recent times is a more robust naval posture to assert its SCS sovereignty and rights.[vii] This has been in the works for some years, with initial experiments carried out to this effect. Notably in May 2018, the PLA Navy, CCG and local maritime law enforcement authorities constituted a joint flotilla to conduct patrols in the Chinese-occupied Paracel Islands for the first time. This arrangement provided for a graduated response to contingencies at sea: if the flotilla were to encounter a foreign naval vessel, the PLAN ship would respond; the CCG ship would deal with foreign fishing vessels; whereas the local authorities focus on Chinese nationals (such as fishermen, smugglers) who violate domestic maritime laws.[viii]

It is plausible to believe that this new arrangement is no longer just confined to the Paracel Islands; instead, it may have already been extended to the Spratly Islands group and other contested features nearby. And incidents since the COVID-19 outbreak appear to have validated this step-up in China’s SCS naval posture. Notably in April 2020 for instance, the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) revealed that in February that year, a PLA Navy ship (identified by its hull number 514, which is the Type-056 missile corvette Liupanshui based in Sanya) exhibited “hostile intent” when it pointed a “radar gun” at a Philippine Navy corvette BRP Conrado Yap close to Commodore Reef within the Philippine-claimed EEZ.[ix]

Though there was no untoward eventuality from the incident, it had become apparent that more than just providing backup for the CCG, the PLA Navy has adopted a more assertive posture in its SCS sovereignty and rights protection missions, and begun to actively challenge rival naval forces in the disputed waters. The Chinese ‘joint flotilla’ patrol arrangement was replicated during the maritime standoff with the Philippines in the West Philippine Sea following the flareup at Whitsun Reef in March 2021. From early March to April 2021, Philippine maritime patrols monitoring the swarm of Chinese vessels in the West Philippine Sea caught sight of PLA Navy vessels around various features that are part of the disputed Spratly Islands group.[x]

That same period, a pair of PLA Navy Type-022 Houbei-class catamaran-hulled missile fast attack craft worked with the CCG to pursue a Filipino television crew conducting investigative journalism in the West Philippine Sea, close to the Second Thomas Shoal where a Filipino military garrison is stationed.[xi] This incident came not long after revelations that a Philippine maritime patrol observed some Houbei craft along with a Type-904 Dayun-class supply tender were spotted at the Chinese-occupied Mischief Reef outpost within what Manila refers to as the West Philippine Sea.[xii] This was another clear sign of the PLA Navy stepping up China’s SCS sovereignty and rights protection posture.

Southeast Asian Pushback: Noteworthy But Hamstrung

Save for Brunei, which has by far yet to be embroiled in any significant SCS standoff with China, the other Southeast Asian parties have had their fair share of resistance, in some form or another, against Beijing’s maritime coercion. For instance, during the February 2020 standoff over the drillship West Capella within the Malaysian exclusive economic zone off Sarawak, the Malaysians deployed at least one ship – usually a naval vessel – as a counter against the more numerous Chinese coastguard presence.[xiii] In June 2021, after a CCG vessel appeared in the Indonesian EEZ to monitor the semi-submersible energy rig Noble Clyde Boudreaux, Jakarta immediately dispatched both naval and coastguard assets to the area in response.[xiv]

Even though China clearly possesses the advantage in terms of its physical force projection in the SCS, given its significant military and coastguard buildup in the area over the years, by no means this asymmetry of maritime forces capabilities and capacities implies its Southeast Asian rivals conceding ground. A noteworthy instance is the Philippines. Following revelations of the Whitsun Reef problem and emergence of numerous Chinese vessels, including naval and coastguard, in the Philippine EEZ in early 2021 Manila responded with vigour which marked a departure from a more passive stance taken during the early days of the then Duterte Administration. Notwithstanding capacity limitations, the Philippine Navy, Coast Guard and Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources mobilized assets and manpower to monitor the situation.[xv]

There were also recorded instances where Philippine maritime forces boldly challenged their Chinese counterparts, despite concerns that the latter could leverage the new Coast Guard Law for retaliation. For instance, in April 2021 the Philippine Coast Guard challenged a group of Chinese fishing vessels, some of which believed to be maritime militia, off Sabina Shoal and expelled them without further incident.[xvi] In July the same year when confronted by a Philippine Coast Guard vessel BRP Cabra and issued a verbal challenge via a long-range acoustic device in waters near Marie Louise Bank (well within the Philippine EEZ), the PLA Navy fleet tug Nantuo 189 departed the area without further incident.[xvii]

The combined quantitative might of the PLA Navy and CCG would put their Southeast Asian rivals at a distinct disadvantage. Southeast Asian military authorities have complained that not only their fleets lack capacity, but those assets in service were already ageing.[xviii] In terms of physical maritime assets, offshore-capable vessels hold the key to persistent presence in the open EEZ waters, not coastal or inshore assets.

As Figure 1 below shows, offshore-capable surface patrol and combat assets that serve navies and coastguards of Southeast Asian SCS parties have largely hovered below 30 percent of the force totals, with Brunei being an exception given its tiny fleet of nine operational vessels. The figure of course does not indicate the exact state of operability and readiness of these assets, and it does not also consider their geographical distribution. Given the long coastlines and vast maritime zones of these Southeast Asian countries (except Brunei), it is only to be expected that the available assets will have to be deployed to other areas besides the SCS.

Figure 1: Surface Patrol and Combat Vessels of Southeast Asian SCS Parties

Source: By author using data compiled from the Military Balance 2022, International Institute of Strategic Studies.

Yet the attempt to address capacity shortfalls in offshore-capable assets has been a chequered and uneven one in Southeast Asia, often determined by funding availability and the tussle between navies and coastguards for finite resources. Vietnam is perhaps one of the most prolific where it comes to maritime forces buildup, having distributed its limited funds to modernize both the navy and its maritime law enforcement agencies – the Coast Guard, and the Fisheries Resources Surveillance Force. The political will, however, is not always matched by the availability of resources and funding. For the other Southeast Asian SCS parties, maritime forces capacity-building has become a less certain prospect given prevailing post-pandemic climate.

Malaysia’s maritime forces development has been hamstrung by economic difficulties, not least the COVID-19 impact as well as procurement governance woes, which placed several key programmes on backburner – not least the Littoral Combat Ship program, which has overrun its envisaged schedule. The first of three Tun Fatimah-class offshore patrol vessels (OPVs) was supposed to have been handed over to the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency in 2019, but would only be delivered earliest in 2022.[xix] The Philippine Navy and Coast Guard have inducted more offshore-capable assets in the form of new frigates and OPVs acquired from France, Japan and South Korea. Funding constraints would prolong the process.

The Way Forward for Southeast Asian Parties

Responding to China’s maritime coercion should not be down to mere vigour while being hamstrung by capacity shortfalls. Oft-cited ways to improve Southeast Asian SCS parties’ ability to push back against China’s maritime coercion include enhancement of maritime domain awareness (MDA). For many of these Southeast Asian countries, real resource limitations in assets and manpower would mean better MDA promises more effective ways of deploying sufficient forces to where it matters most. Over the recent decade, Southeast Asian SCS parties has been a primary beneficiary to U.S.-sponsored maritime security capacity-building assistance, which in large part focuses on plugging MDA gaps, and facilitate to an extent their optimal deployment of limited maritime capacities for sovereignty assertion in the vast SCS.

Given that China has committed its coastguard forces as spearheads on the SCS frontline, there has been a longstanding push for Southeast Asian countries to expand their coastguards instead of devoting too much attention to navies. Such concerns were grounded on the assumptions that Beijing would only commit the CCG (and for that matter, its maritime militia) to the SCS operations. As highlighted earlier, given China’s more assertive use of its navy in pushing SCS maritime sovereignty and rights, Southeast Asian maritime forces capacity-building should focus on not only MDA, but beefing up physical assets of both navies and coastguards that allow for action against transgressors at sea – not least of course, putting up a viable counter-presence against China’s in the disputed waters.

At present, extra-regional powers are gradually scaling up the game where it comes to supply of physical assets besides MDA, such as the case of the transfers of former U.S. Coast Guard cutters to Vietnam, Japan’s provision of used and newbuild OPVs to Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam. Yet there remains outstanding needs for Southeast Asian SCS parties to fill this capacity gap. The asymmetry in maritime force levels between these countries and China looks set to persist. Transfers and newbuild constructions aside, measures to help these Southeast Asian countries spruce up their local shipbuilding capacities, such as through funding, technology transfers and other technical assistance will be helpful in allowing them to become more self-sufficient in building their own OPVs.

Physical capabilities to push back against China’s maritime coercion is one thing though, other pressing aspects quite another. Given the blurring nexus between China’s naval and coastguard forces in the SCS, it becomes all the more imperative upon Southeast Asian countries to relook into and enhance their inter-agency maritime efforts. One may take comfort in the fact that some of the Southeast Asian SCS parties have recognized and getting started in improving on this aspect.[xx] Still, it remains a long, uneven road of work in progress across these Southeast Asian players. It is therefore important to give a renewed emphasis on this dimension.

Collin Koh Swee Lean is research fellow at the Maritime Security Programme, at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University, based in Singapore. He primarily researches on Indo-Pacific maritime security and naval affairs, focusing especially on Southeast Asia.

[i] The PLA Navy’s latest aircraft carrier is the Fujian, but its homeport has yet to be decided since its launch in June 2022. Hence, the only Chinese carrier homeported in the SCS is the Shandong. “China's new aircraft carrier enters service at South China Sea base,” Reuters, 17 December 2019.

[ii] “Xi attends commissioning of 3 naval vessels, signaling ‘China’s determination to manage S. China Sea’,” Global Times, 24 April 2021.

[iii] For example, see 宋志伟 [Song Zhiwei], “中国海警在南海有争议海区执法的几点思考,” [Some Points for Consideration Regarding China Coast Guard’s Law Enforcement in the South China Sea Disputed Areas], 公安海警学院学报 [Journal of the Chinese Maritime Police Academy], Vol. 12, No. 4 (May 2013), pp. 48–50; 潘志煊 [Pan Zhixuan], 何忠龙 [He Zhonglong] and 王河 [Wang He], “论南海局势下中国海警的机遇与挑战,” [A Discussion on the Opportunities and Challenges Facing China Coast Guard under the Current South China Sea Situation], 公安海警学院学报 [Journal of the Chinese Maritime Police Academy], Vol. 10, No. 4 (October 2013), pp. 48–51; 周晓成 [Zhou Xiaocheng], “中国海警南海海域维权力量运用研究,“ [A Study on the Application of China Coast Guard’s Right Protection Forces in the South China Sea], 武警学院学报 [Journal of the Armed Police Academy], Vol. 32, No. 11 (November 2016), pp. 15–18.

[iv] See for example: “RMN chases out 12 foreign fishing boats,” Bernama, 17 March 2022; “TNI AL Tangkap Dua Kapal Ikan Vietnam di Laut Natuna Utara,” [Indonesian Navy seizes two Vietnamese fishing vessels in the North Natuna Sea], CNN Indonesia, 27 July 2022.

[v] Against the CCG’s commonly used stable of OPVs that typically displace 1,000-2,000 tons, the Southeast Asian SCS parties could muster equivalent ships of similar displacement bracket, such as the case of the Royal Malaysian Navy with its Kedah-class patrol vessel which would not be fitted with missiles but merely with gun armament for peacetime, constabulary missions in the SCS. The standard main gun armament of Southeast Asian rival navies would be a medium-calibre type of 57-76mm, which is bigger than the typically 25-35mm type mounted on most of the CCG vessels.

[vi] The PLAN reportedly began transferring its earlier-built Type-056 Jiangdao-class guided missile corvettes to the CCG, keeping only the improved Type-056A optimized for anti-submarine warfare duties. Upon the transfer, the Type-056 would have their missile armaments and associated sensors and fire control systems removed, retaining the gun armaments while being painted in CCG colours. “China Transferring Navy Type 056 Corvettes to the Coast Guard,” Naval News, 24 December 2021.

[vii] The concerns about Southeast Asian SCS rivals deploying naval forces against the CCG spearheading its presence in the disputed waters, have been raised within the Chinese coastguard community (see footnote 3). In addition, recent maritime face-offs between Chinese and Southeast Asian parties in the SCS saw CCG confronting the counter-presence put up by naval forces. In the 2020 standoff over West Capella, the Malaysians deployed a navy frigate to confront the CCG (such as the case of Royal Malaysian Navy frigate KD Jebat against the Haijing 5203) because it is one of the biggest, ocean-capable assets that could more effectively put up a counter-presence against the Chinese near the drillship. “Malaysia Picks a Three-Way Fight in the South China Sea,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, February 21, 2020, at: https://amti.csis.org/malaysia-picks-a-three-way-fight-in-the-south-china-sea/

[viii] “军警民联合编队首次巡逻西沙岛礁,历时5天4夜,” [Military-coastguard-civilian joint flotilla conducts maiden Paracel Islands patrol, lasting 5 days and 4 nights], 中国军网 [81.cn], 20 May 2018.

[ix] The Filipino warship did not have the electronic support measures to confirm electromagnetic emissions, but by “radar gun” it was actually referring to the PLA Navy ship’s fire control radar system for the main gun mounted on the forecastle, and the pointing was observed visually. Priam Nepomuceno, “Wescom confirms Chinese vessel’s hostile act vs. PH Navy ship,” Philippine News Agency, 23 April 2020.

[x] The National Task Force on the West Philippine Sea (NTF-WPS) spotted a pair of Type-022 Houbei-class catamaran-hulled missile fast attack craft and a “corvette class warship” – most likely the Type-056. “4 Chinese Navy ships, 254 maritime militia vessels 'swarm' Spratlys, West Philippine Sea–NTF-WPS,” Manila Standard, 31 March 2021; “Patrols reveal 6 China navy ships, 240 militia in West Philippine Sea,” GMA News, 13 April 2021.

[xi] The Filipino vessel was chartered by the ABS-CBN News agency and was sailing close to the Philippine-garrisoned Second Thomas Shoal (Ayungin Reef) when it was first chased by the CCG patrol vessel CCG5101 which was then joined by the pair of PLAN Houbei craft. See Chiara Zambrano, “Filipino vessel chased down by 2 Chinese missile attack craft in West PH Sea,” ABS-CBN News, 9 April 2021; and Chiara Zambrano, “LOOK: Chinese vessels hound Philippine fishing boat,” ABS-CBN News, 9 April 2021.

[xii] Frances Mangosing, “3 China war vessels park at Panganiban Reef inside PH EEZ,” Inquirer.net, 1 April 2021.

[xiii] “Malaysia Picks a Three-Way Fight in the South China Sea,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, February 21, 2020, at: https://amti.csis.org/malaysia-picks-a-three-way-fight-in-the-south-china-sea/

[xiv] “Nervous Energy: China Targets New Indonesian, Malaysian Drilling,” Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, November 12, 2021, at: https://amti.csis.org/nervous-energy-china-targets-new-indonesian-malaysian-drilling/

[xv] Jairo Bolledo, “More ships sent to West PH Sea amid continuous Chinese incursion,” Rappler, 13 April 2021.

[xvi] Glee Jalea, “How the Philippine Coast Guard challenged Chinese vessels in Sabina Shoal,” CNN Philippines, 6 May 2021.

[xvii] Raymond Carl Dela Cruz, “PCG drives away Chinese Navy ship from Marie Louise Bank in WPS,” Philippine News Agency, 19 July 2021; Frances Mangosing, “PH Coast Guard stops China navy incursion near Palawan resort town,” Inquirer.net, 19 July 2021. Pictures of the close encounter at Marie Louise Bank can be found in this Manila Bulletin report: Richa Noriega, “PH Coast Guard’s radio challenge drives away Chinese Navy warship in WPS,” Manila Bulletin, 19 July 2021.

[xviii] See for instance, Joviland Rita, “Philippine naval ships, other assets deployed in West Philippine Sea not enough —Sobejana,” GMA News, 22 April 2021; Farik Zolkepli, “Navy's transformation plan needs to be tweaked due to recent events, says Navy Chief,” The Star (Malaysia), 27 April 2022.

[xix] “MMEA hoping to receive OPV this year,” Bernama, 7 June 2022.

[xx] For example, the Philippine Navy and Coast Guard have been improving their cooperation to “harmonize operations” in securing the country’s maritime rights, and this interagency effort culminated most notably in their first joint exercise PAGKAKAISA in November 2019. The Malaysian Armed Forces have also been exercising more regularly with the Malaysian Maritime Enforcement Agency (MMEA) in the SCS, such as the case of Exercise Taming Sari in August 2021. Priam Nepomuceno, “PH Navy, Coast Guard conduct 1st joint exercise,” Philippine News Agency, 21 November 2019; Priam Nepomuceno, “Navy, Coast Guard to boost cooperation in protecting PH waters,” Philippine News Agency, 11 November 2020; M. Daim, “Eks Taming Sari 20/21: TLDM pamer keupayaan gempur sasaran di Laut China Selatan,” [Exercise Taming Sari 20/21: Royal Malaysian Navy shows off strike capability in the South China Sea], Air Times, 12 August 2021.

Comments (0)

Same category

© 2016 Maritime Issues