Extended Continental Shelf: A Renewed South China Sea Competition

The 2019 Malaysian partial CLCS submission renewed the legal exchanges over the South China Sea. Most of the claimants, except China and Brunei, through their statements and actions, expressed acceptance and support for the 2016 Tribunal Award.

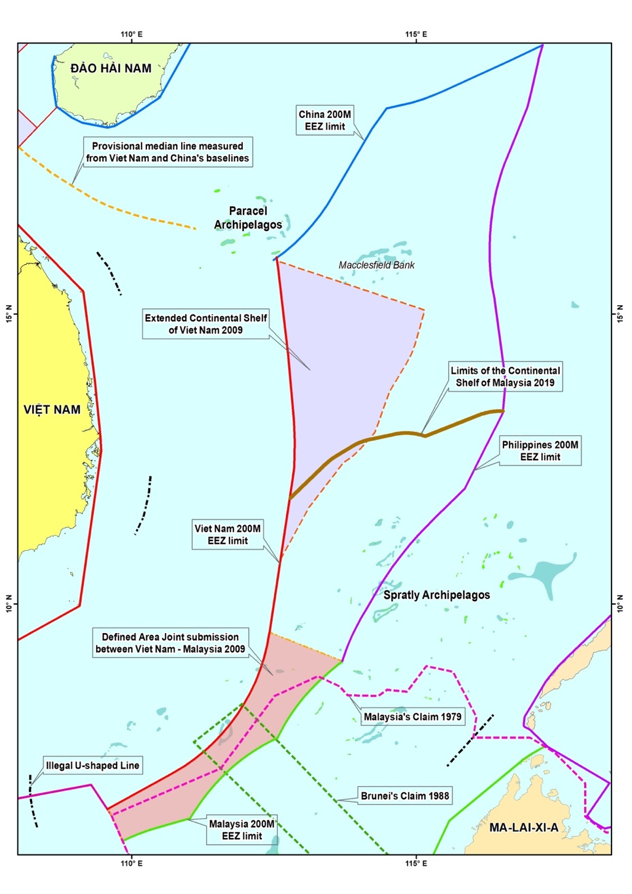

In 2009, Malaysia - Vietnam Joint Submission and Vietnam’s Partial Submission on 6 and 7 May respectively, created a turning point in the legal battle in the South China Sea. They were considered as legitimate undertakings in implementing Article 76 (8) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982 (UNCLOS) as well as the Rules of Procedure of the Commission of the Limits of the Continental shelf (CLCS). Both submissions came before the deadline of 13 May, which is fixed by the States Parties to UNCLOS. These two submissions forced claimant States to gradually clarify their positions on the legal status of features and the limits of their claims in the South China Sea. Neither of these submissions considered the possibility that the features of the Spratly Islands may have their own continental shelf.

On 7 May 2009 China issued a diplomatic protest with the nine-dash line map attached. This was the first time this map, which claims almost all of the South China Sea, including features and waters within it under Chinese sovereignty, has been presented within the framework of the United Nations. It implies that there are no extended continental shelves in the South China Sea. Instead of joining the Vietnam-Malaysia joint submission, the Philippines issued a separate diplomatic protest on 4 August 2009 emphasizing their stance on Kalayaan Islands Group (KIG) and North Borneo. In 2009, Indonesia, which often regards itself as a non-claimant State in the matter, also spoke out and rejected the validity of the Chinese nine dash line. The 2009 diplomatic note exchanges underlined the importance of clarifying the legal status of the features in the Spratly Islands, which served as the premise for the Philippines to initiate arbitral proceeding against China in 2013.

The 2016 arbitration verdict laid grounds for the second diplomatic note war in 2019-2020. On 12 December 2019, Malaysia’s diplomatic note extended the outer limit of the continental shelf based on the assumption that high tide features in the Paracel and Spratly Islands are only entitled to 12 nm territorial seas and that the nine-dash line has no legal merit. Given that the verdict favoured the Philippines, and even though it was not a party to the lawsuit, Malaysia saw an opportunity to benefit from the ruling, as such stance extended Malaysia’s continental shelf almost two times of its 1979 claim.

In 2020, the Philippines added greater clarity to its position. Whilst the 2009 note emphasized that the Malaysia - Vietnam joint submission overlaps with the continental shelf of the Philippines and makes “controversy arising from the territorial claims on some islands in the area including North Borneo”, the diplomatic note issued on 6 March 2020 confirmed the conclusions of the 2016 Tribunal Ruling that “none of the high tide features in the Spratly Islands generate entitlements to an exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” The Philippines also expressed its consistent rejection of the Chinese nine-dash line claim, historic rights and the notion of "adjacent waters as well as the seabed and subsoil underground.” The 2020 diplomatic note show that the Philippines did not give up the arbitration ruling, and it continues to bring it up when it sees fit in dealing with neighboring countries.

The Chinese diplomatic notes sent to the United Nations with regard to those of Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam respectively on 12 December 2019, 23 March and 17 April 2020, do not mention the nine-dash line, which was the main subject of, and was rejected by, the South China Sea Arbitration. Instead, in the note to Malaysia, it claimed Nanhai Zhudao, which consists of Dongsha Quindao, Xisha Quindao, Zhongsha Quindao and Nansha Quindao. This concept was stated in the 2014 Chinese “Position Paper on the Matter of Jurisdiction in the South China Sea Arbitration Initiated by the Republic of the Philippines”; in the 2016 “Statement of the Government of the PRC on China's Territorial Sovereignty and Maritime Rights and Interests in the South China Sea”; and earlier in the 1992 Chinese Law on the territorial law and the contiguous zone. It was reportedly rebranded as “Four Shas” in an exchange between Chinese officials and US State Department counterparts in 2017.

By claiming maritime zones based on the Nanhai Zhudao, China expected to legitimize its claims using UNCLOS terminologies. However, this concept is as ambiguous as the nine-dash line. By using the singular instead of the plural in the statement that "China has exclusive economic zone and continental shelf based on Nanhai Zhudao", China might imply that even Nanhai Zhudao can be considered as a single unit and thereby the archipelagic baseline could be drawn for Nanhai Zhudao by joining the outermost points of their respective outermost features, and not just for each archipelago as already did in Paracels. However, in the notes addressing to the Philippines and Vietnam, China repeated its claims sovereignty over the Paracels and Spratlys, and their adjacent waters. China claims sovereign rights and jurisdiction over the relevant waters as well as seabed and subsoil thereof. It can also be interpreted that China also reserves the possibility to draw archipelagic baseline for each archipelago in Nanhai Zhudao. Either way, China benefits by rejecting the arbitration ruling as well as establishing new claims. The Chinese note verbale on 23 March 2020 continues the position of three no(s), namely: do not participate; do not accept the jurisdiction of the Tribunal; and do not recognize the arbitration award, given that China "never accepts any claim or action based on the awards.” China continues to put efforts in preventing other countries from using the verdict to support their positions whilst at the same time persisting to claim historic rights in the South China Sea. It also argues that those rights are above the rights provided by UNCLOS, contrary to what the arbitration has ruled.

The 2020 note stated that “China and the Philippines have reached consensus on properly addressing issues on the South China Sea arbitration and have returned to the right track of settling maritime issues through bilateral friendly negotiation and consultation.” This sentence raises doubts that the Philippines and China have reached an implicit agreement to ignore the validity of the ruling. However, it does not provide any further evidence about the said consensus. The most recent agreement that the two countries publicly announced was the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation on Oil and Gas Development, signed in November 2018 for a period of one year and nowhere did it mention agreeing to disregard the arbitration ruling. The MOU is also not legally binding. It neither affects the legal positions of each party nor creates rights or obligations under international law or domestic law. The argument of the consensus on the properly addressing issues on the South China Sea arbitration could be used for the aim to accuse the inconsistency of the Philippines position.

The Chinese note of 17 April 2020 has a new point. Instead of demanding Vietnam “to stop its acts of violating China’s sovereignty”, China requires Vietnam to “withdraw all the crews and facilities from the islands and reefs it has invaded and illegally occupied.” China, the only one state used the force in 1974 and 1988, has accused Vietnam of violating the purpose and principles of the Charter of the United Nations. It can be regarded as signals that China may increase coercions or resort to force on the ground against other claimant countries. Making the matter worse, on 18 April 2020, China announced the establishment of Xisha District and Nansha District. The former has the authority based in Woody Island and administering the Paracel & "Zhongsha" (include Macclesfield Bank, the main part of Zhongsha and the Scarborough Shoal) features and waters. The latter has the government based in Fiery Cross Reef and administering the Spratly features and waters.

Figure 1: The Map of the Claims in the South China Sea

The map is prepared by Nguyen Hong Thao and Nguyen Duy Luong. All rights are reserved.

Vietnam’s position is reflected on the statement of the MOFA spokesperson on 9 January 2020 and its notes verbales to the United Nations on 30 March and 10 April 2020 in response to the notes of China, Malaysia and Philippines respectively. They clarify in a systematic manner Vietnam’s position on maritime entitlements in the South China Sea under UNCLOS in general and after the arbitration award specifically. It is affirmed that UNCLOS provides the sole legal basis for defining, in a comprehensive and exhaustive manner, the scope of their respective maritime entitlements in the East Sea, the Vietnamese name for the South China Sea, implicitly rejecting the nine-dash line claim and historical rights of China in the South China Sea. Vietnam contends that “maritime entitlement of each high-tide feature in the Hoang Sa (Paracel) Islands and the Truong Sa (Spratly) Islands shall be determined in accordance with Article 121(3) of UNCLOS.” In the its joint submission with Malaysia, Vietnam extended the continental shelf beyond 200 nm from the mainland with the assumption that the features of Spratly Islands did not have its own continental shelf. In the 2014 note sent to the Arbitral Tribunal for the purpose of recognition of its jurisdiction, Vietnam underlined that “none of the features mentioned by the Philippines in the proceedings can enjoy their own exclusive economic zone and continental shelf or generate maritime entitlements in excess of 12 nautical miles since they are low tide elevations and ‘rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own’ under Article 121 (3) of the Convention.” The summary of these statements and the Vietnam-Malaysia joint submission of 2009 shows Vietnam's support for the conclusions of the verdict, specifically that “none of the high-tide features in the Spratly Islands are capable of sustaining human habitation or an economic life of their own within the meaning of those terms in Article 121(3) of the Convention.” The legal status of Paracel Islands will be determined in accordance with Article 121 (3) of UNCLOS and Article 20 of the Law of the Sea of Vietnam in 2012.

The note on 10 April 2020 and the statement of 9 January 2020 reserve sovereign rights and jurisdictions of Vietnam over the continental shelf extending beyond 200 nm in the South China Sea. Vietnam's 2020 notes continue to oppose the application of archipelagic baselines to the Paracel and Spratly Islands, explicitly refuting Chinese straight baseline system around the Paracel Islands announced in 1996 and pre-empting same practice being used for the Spratlys. Vietnam considers that low-tide elevations or submerged features are not subject of appropriation and do not, in and of themselves, generate entitlements to any maritime zones. Maritime claims in the South China Sea that exceed the limits provided in UNCLOS, including historic rights, are unlawful. Viet Nam also reiterates its consistent position that Viet Nam has ample historical evidence and legal basis to affirm its sovereignty over the Hoang Sa (Paracel) Islands and the Truong Sa (Spratly) Islands in accordance with international law. Unlike those of China and the Philippines, Vietnam’s note did not request the CLCS stopping consideration of the submissions. It opens to the possibility of negotiation on that matter to reach a joint submission in the future.

In a snapshot, the 2019 Malaysian partial submission renewed the legal exchanges over the South China Sea. Most of the claimants, except China and Brunei, through their statements and actions, expressed acceptance and support for the 2016 Tribunal Award. The dispute in the South China Sea is not confined to the contest over overlapping exclusive economic zones and continental shelves but also include disputes over extended continental shelves. Since 14 April 2020, Chinese Geological Survey Vessel No.8 (Haiyang Dizhi 8) has been sent to the southern part of the South China Sea which are considered within Malaysia and Brunei’s Exclusive Economic Zones under UNCLOS. The situation requires negotiations between concerned States and the coordination of the CLCS in reviewing submissions made by the states. The new round of note exchange indicates a tendency that small claimant states put premium on legal means to address the disputes rather threats or use of force. The claims to extended continental shelf will also raise the question of management of biologic resources in the water columns over this area. In other words, the South China Sea may have a portion under the legal status of High Seas outside the exclusive economic zones of coastal states. To determine the scope of the High Seas, concerned States must officially delineate their respective limits of economic exclusive zones in accordance with UNCLOS. However, the question of whether there is a seabed - the common heritage of mankind in the middle of the South China Sea - remains open. The legal status of South China Sea features will depend on the legal battle that has been triggered rather than with coercions or the use of force.

Nguyen Hong Thao is an Associate Professor of International Law at the National University of Hanoi and Diplomatic Academy of Vietnam.

Click here for pdf file