DOC and COC - Best Path to Keep Waters Calm

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the signing of the DOC, a special year for China and ASEAN countries who are committed to peace and stability as well as maritime cooperation in the South China Sea. Taking this as an opportunity, they need to review their experience and learn lessons. Starting with building consensus and enhancing mutual trust, they need to focus on new ideas and new paths and, guided by win-win cooperation, write a new chapter on maritime cooperation and ocean governance in the South China Sea.

By Wu Shicun

March 3, 2023

Against the backdrop of the lingering Covid-19, the Russia-Ukraine crises, and geopolitical conflicts in various forms, the South China Sea face many uncertainties and dilemmas in cooperation at sea.

First, the new and biased U.S. policy towards the South China Sea is the biggest external factor undermining peace and stability in the South China Sea. Since it gave up its neutrality on the South China Sea in 2020, the United States has been moving faster in building “a modular alliance and partnership system” and conducting strategic encirclement of China through four major mechanisms—the Quad Security Dialogue with Japan, India and Australia, which just concluded this year’s summit meeting in Tokyo, the AUKUS military alliance with the United Kingdom and Australia, the alliance with Japan, and cooperation with the Philippines. The focus is on the military containment of China. In the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, the above “minilateral” security cooperation mechanisms have different yet overlapped priorities and divisions of labor. Among them, the Quad shows signs of expanding into the South China Sea. The United States, the Philippines and some South China Sea littoral countries are making step-by-step progress in their institutional and regular cooperation on maritime intelligence sharing, base use, equipment support and policy coordination on the South China Sea.

Second, the U.S. military presence and activities under the framework of its new Indo-Pacific military strategy are the biggest driving force in the militarization in the South China Sea. The Biden Administration aims to build an equilibrium of influence to the U.S. preferences and values. It has launched new military programs such as “integrated deterrence” and “Pacific deterrence” to step up deployment of strategic forces in the South China Sea and surrounding areas. In militarizing the South China Sea, the United States has conducted forward deployments, military exercises, freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), and close-in reconnaissance operations and other activities targeted at China in the South China Sea. As a result, interaction between China and the United States is evolving into strategic confrontation featuring deterrence and counter-deterrence, reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance, and control and counter-control. In addition, the United States sends one nuclear-powered submarine and one aircraft carrier task force to the South China Sea every month on average. A series of U.S. moves are undermining the strategic balance in the South China Sea and surrounding areas, making China-U.S. military competition increasingly white-hot, and triggering an arms race in Southeast Asia and other parts of the Indo-Pacific region on conventional weapons, including submarines, missiles and air defense systems.

Third, unilateral actions by some claimant countries, particularly oil and gas development and island expansion in disputed waters, are the main internal cause of tensions in the South China Sea. In the past three years, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia have carried out unilateral oil and gas development activities in the contested areas of the Nansha Islands. Unilateral actions at sea by claimant countries tend to trigger security emergencies featuring confrontation between military, police and civil law enforcement forces, which will undoubtedly have a negative impact on bilateral relations.

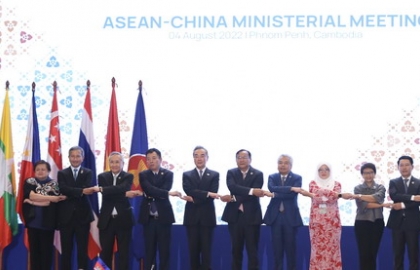

In 2002, China and ten ASEAN countries signed the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, after more than six years of negotiations. Under the DOC framework, China and ASEAN countries have carried out a series of practical cooperation at the multilateral and bilateral levels. For example, at the multilateral level, they set up a hotline platform for senior diplomats to respond to maritime emergencies, conducted joint maritime search and rescue exercises, launched a marine emergency hotline, and built a marine search and rescue information platform. At the bilateral level, for example, China and the Philippines have set up a bilateral consultation mechanism on the South China Sea, and, since 2016, conducted regular cooperation in such fields as fish farming and maritime law enforcement. Therefore, in the 20 years since the signing of the DOC, all parties have reaped some impressive early harvests in such fields as enhancing mutual trust, conducting practical cooperation at sea, and managing crisis, demonstrating its unquestioned and special contribution to the generally stable and controllable South China Sea.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the signing of the DOC, a special year for China and ASEAN countries who are committed to peace and stability as well as maritime cooperation in the South China Sea. Taking this as an opportunity, they need to review their experience and learn lessons. Starting with building consensus and enhancing mutual trust, they need to focus on new ideas and new paths and, guided by win-win cooperation, write a new chapter on maritime cooperation and ocean governance in the South China Sea.

First, we need to explore a new path for joint development with new ideas and cooperation models. Joint development is the only way to for claimant countries to develop oil and gas resources in disputed areas and share benefits. When it comes to major differences between claimant countries on issues such as benefit sharing, management model, applicable law and maritime claims, they can depoliticize or play down sensitive narrative and introduce new approaches such as registering companies in third countries as operating entities. By minimizing claims and maximizing cooperation, they can take faster steps to translate the vision of joint development to reality in the South China Sea for the benefit of all parties.

Second, we need to hold high the banner of the DOC and make maritime cooperation the general trend at sea. The five areas of practical maritime cooperation proposed in the DOC are all urgent matters for sustainable development and ocean governance in the South China Sea. Especially, eco-environmental protection, humanitarian search and rescue, and waterway safety represent shared interests and responsibilities of all countries in this region. China and ASEAN countries can start cooperation in low-sensitive, in-demand and easy-to-operate fields. For example, they can set up a joint inter-governmental steering committee, eminent persons and expert groups; sign a South China Sea environmental protection convention; and build institutions such as a cooperation mechanism for coastal states in the South China Sea, providing sustained support for regional cooperation on ocean governance.

Third, a new and consensus-oriented road map needs to be formulated, phase by phase and step by step, for the negotiations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC). The COC will play an unquestionably important role in realizing long-term peace and stability in the South China Sea and building regional maritime rules and order. Major outcomes have been made in earlier negotiations. However, recently, the United States, Japan and some other non-resident countries interfered with the COC talks without justifications; and some claimant countries hesitated in formulating the COC out of the need for unilateral actions to consolidate and expand their vested interests. With such internal and external factors, the consultations have achieved little progress despite the rhetoric, and lose steam to move ahead. Aware of the current situation, China and ASEAN countries need to seize the window of opportunity given the relative tranquility recently in the South China Sea. They can divide big issues into smaller ones, take small yet quick steps, start with easier questions before tackling difficult ones, and assign tasks, in order to create favorable conditions for the conclusion of the COC.

COC consultations will not only mean incomplete implementation of the DOC, but also affect political mutual trust between China and ASEAN countries. Unilateral actions on the South China Sea issue will disrupt the relations between China and other claimants. The South China Sea will once again become an arena for great power competition.

From my perspective, the only way to avoid the above-mentioned possibilities is to take a more practical approach to maritime cooperation under the DOC framework, while moving faster in building rules and security mechanisms in the South China Sea through the COC consultations, with the ultimate aim of enduring peace and stability in the South China Sea. The COC consultations are a joint mission for China and the 10 ASEAN countries; the COC, once adopted, will help realize stable China-ASEAN relations in the long run; and consensus on the COC will make the stakeholders of the South China Sea issue the beneficiaries. At this stage, we need to aim at increasing mutual trust, building consensus, and seeking common ground while reserving differences in the COC consultations. In a sense, formulating the COC is like members of a big family setting rules of conduct by themselves to restrain themselves. High-level and candid consultations cannot move forward without mutual trust. Consensus is the logical starting point, providing essential conditions for building a multilateral mechanism. Without consensus, when you want to move forward, others may go the opposite way. Therefore, the COC consultations will not be substantive without consensus. With different strategic considerations, interests and requests among the 11 countries on the South China Sea issue, it is inevitable for them to argue and even quarrel with each other. In this case, "seeking common ground while reserving differences" as well as necessary concessions or compromises are both the art of diplomatic negotiation and the "rules of procedure" to advance the consultations.

In short, the DOC implementation and the COC consultations are the only choice for China and ASEAN countries to build a beautiful home together in the South China Sea. Only by forging ahead toward the shared goal and overcoming difficulties will we successfully conclude the COC consultations.

Wu Shicun is founding president, director of academic committee and senior research fellow of China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies. He also serves as chairman of board of directors of the China-Southeast Asia Research Center on the South China Sea, chairman of the advisory board of Institute for China-America Studies, vice president of the China Institute for Free Trade Ports Studies, and adjunct professor of Nanjing University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

First, the new and biased U.S. policy towards the South China Sea is the biggest external factor undermining peace and stability in the South China Sea. Since it gave up its neutrality on the South China Sea in 2020, the United States has been moving faster in building “a modular alliance and partnership system” and conducting strategic encirclement of China through four major mechanisms—the Quad Security Dialogue with Japan, India and Australia, which just concluded this year’s summit meeting in Tokyo, the AUKUS military alliance with the United Kingdom and Australia, the alliance with Japan, and cooperation with the Philippines. The focus is on the military containment of China. In the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy, the above “minilateral” security cooperation mechanisms have different yet overlapped priorities and divisions of labor. Among them, the Quad shows signs of expanding into the South China Sea. The United States, the Philippines and some South China Sea littoral countries are making step-by-step progress in their institutional and regular cooperation on maritime intelligence sharing, base use, equipment support and policy coordination on the South China Sea.

Second, the U.S. military presence and activities under the framework of its new Indo-Pacific military strategy are the biggest driving force in the militarization in the South China Sea. The Biden Administration aims to build an equilibrium of influence to the U.S. preferences and values. It has launched new military programs such as “integrated deterrence” and “Pacific deterrence” to step up deployment of strategic forces in the South China Sea and surrounding areas. In militarizing the South China Sea, the United States has conducted forward deployments, military exercises, freedom of navigation operations (FONOPs), and close-in reconnaissance operations and other activities targeted at China in the South China Sea. As a result, interaction between China and the United States is evolving into strategic confrontation featuring deterrence and counter-deterrence, reconnaissance and counter-reconnaissance, and control and counter-control. In addition, the United States sends one nuclear-powered submarine and one aircraft carrier task force to the South China Sea every month on average. A series of U.S. moves are undermining the strategic balance in the South China Sea and surrounding areas, making China-U.S. military competition increasingly white-hot, and triggering an arms race in Southeast Asia and other parts of the Indo-Pacific region on conventional weapons, including submarines, missiles and air defense systems.

Third, unilateral actions by some claimant countries, particularly oil and gas development and island expansion in disputed waters, are the main internal cause of tensions in the South China Sea. In the past three years, Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia have carried out unilateral oil and gas development activities in the contested areas of the Nansha Islands. Unilateral actions at sea by claimant countries tend to trigger security emergencies featuring confrontation between military, police and civil law enforcement forces, which will undoubtedly have a negative impact on bilateral relations.

In 2002, China and ten ASEAN countries signed the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea (DOC) in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, after more than six years of negotiations. Under the DOC framework, China and ASEAN countries have carried out a series of practical cooperation at the multilateral and bilateral levels. For example, at the multilateral level, they set up a hotline platform for senior diplomats to respond to maritime emergencies, conducted joint maritime search and rescue exercises, launched a marine emergency hotline, and built a marine search and rescue information platform. At the bilateral level, for example, China and the Philippines have set up a bilateral consultation mechanism on the South China Sea, and, since 2016, conducted regular cooperation in such fields as fish farming and maritime law enforcement. Therefore, in the 20 years since the signing of the DOC, all parties have reaped some impressive early harvests in such fields as enhancing mutual trust, conducting practical cooperation at sea, and managing crisis, demonstrating its unquestioned and special contribution to the generally stable and controllable South China Sea.

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the signing of the DOC, a special year for China and ASEAN countries who are committed to peace and stability as well as maritime cooperation in the South China Sea. Taking this as an opportunity, they need to review their experience and learn lessons. Starting with building consensus and enhancing mutual trust, they need to focus on new ideas and new paths and, guided by win-win cooperation, write a new chapter on maritime cooperation and ocean governance in the South China Sea.

First, we need to explore a new path for joint development with new ideas and cooperation models. Joint development is the only way to for claimant countries to develop oil and gas resources in disputed areas and share benefits. When it comes to major differences between claimant countries on issues such as benefit sharing, management model, applicable law and maritime claims, they can depoliticize or play down sensitive narrative and introduce new approaches such as registering companies in third countries as operating entities. By minimizing claims and maximizing cooperation, they can take faster steps to translate the vision of joint development to reality in the South China Sea for the benefit of all parties.

Second, we need to hold high the banner of the DOC and make maritime cooperation the general trend at sea. The five areas of practical maritime cooperation proposed in the DOC are all urgent matters for sustainable development and ocean governance in the South China Sea. Especially, eco-environmental protection, humanitarian search and rescue, and waterway safety represent shared interests and responsibilities of all countries in this region. China and ASEAN countries can start cooperation in low-sensitive, in-demand and easy-to-operate fields. For example, they can set up a joint inter-governmental steering committee, eminent persons and expert groups; sign a South China Sea environmental protection convention; and build institutions such as a cooperation mechanism for coastal states in the South China Sea, providing sustained support for regional cooperation on ocean governance.

Third, a new and consensus-oriented road map needs to be formulated, phase by phase and step by step, for the negotiations on the Code of Conduct in the South China Sea (COC). The COC will play an unquestionably important role in realizing long-term peace and stability in the South China Sea and building regional maritime rules and order. Major outcomes have been made in earlier negotiations. However, recently, the United States, Japan and some other non-resident countries interfered with the COC talks without justifications; and some claimant countries hesitated in formulating the COC out of the need for unilateral actions to consolidate and expand their vested interests. With such internal and external factors, the consultations have achieved little progress despite the rhetoric, and lose steam to move ahead. Aware of the current situation, China and ASEAN countries need to seize the window of opportunity given the relative tranquility recently in the South China Sea. They can divide big issues into smaller ones, take small yet quick steps, start with easier questions before tackling difficult ones, and assign tasks, in order to create favorable conditions for the conclusion of the COC.

COC consultations will not only mean incomplete implementation of the DOC, but also affect political mutual trust between China and ASEAN countries. Unilateral actions on the South China Sea issue will disrupt the relations between China and other claimants. The South China Sea will once again become an arena for great power competition.

From my perspective, the only way to avoid the above-mentioned possibilities is to take a more practical approach to maritime cooperation under the DOC framework, while moving faster in building rules and security mechanisms in the South China Sea through the COC consultations, with the ultimate aim of enduring peace and stability in the South China Sea. The COC consultations are a joint mission for China and the 10 ASEAN countries; the COC, once adopted, will help realize stable China-ASEAN relations in the long run; and consensus on the COC will make the stakeholders of the South China Sea issue the beneficiaries. At this stage, we need to aim at increasing mutual trust, building consensus, and seeking common ground while reserving differences in the COC consultations. In a sense, formulating the COC is like members of a big family setting rules of conduct by themselves to restrain themselves. High-level and candid consultations cannot move forward without mutual trust. Consensus is the logical starting point, providing essential conditions for building a multilateral mechanism. Without consensus, when you want to move forward, others may go the opposite way. Therefore, the COC consultations will not be substantive without consensus. With different strategic considerations, interests and requests among the 11 countries on the South China Sea issue, it is inevitable for them to argue and even quarrel with each other. In this case, "seeking common ground while reserving differences" as well as necessary concessions or compromises are both the art of diplomatic negotiation and the "rules of procedure" to advance the consultations.

In short, the DOC implementation and the COC consultations are the only choice for China and ASEAN countries to build a beautiful home together in the South China Sea. Only by forging ahead toward the shared goal and overcoming difficulties will we successfully conclude the COC consultations.

Wu Shicun is founding president, director of academic committee and senior research fellow of China’s National Institute for South China Sea Studies. He also serves as chairman of board of directors of the China-Southeast Asia Research Center on the South China Sea, chairman of the advisory board of Institute for China-America Studies, vice president of the China Institute for Free Trade Ports Studies, and adjunct professor of Nanjing University and Shanghai Jiao Tong University.

Comments (0)

Same category

© 2016 Maritime Issues